A Green Kurdistan Project: A Climate Crisis Report

The changes in the climate have been so swift in places like Iraq, they have led international agencies to sound the alarm over expectations of a major environmental crisis if they were to be left unaddressed. Some reports have suggested that the consequences of this crisis could be worse than destruction brought on by conflicts, including the devastating outcome of the latest Islamic State (ISIS) war. Research and reports on this are not scarce in international media outlets, some of which have linked one aspect of the outbreak of conflicts and the rise of extremist groups to the political, economic and psychological impacts of the deepening climate crisis.

The climate crisis brings with itself droughts, desertification, flooding and forced migration, which are likely to push political, ideological and ethnic tensions to the brink of conflict between states and non-state actors.

Rising tensions and violence

A 2017 report by National Geographic analyzed how the devastating impact of the climate crisis coupled with water scarcity in Iraq had driven ISIS recruitment at the tip of that bloody conflict. Another major problem is that extremist ideology tend to gain ground in times of crisis, especially when groups holding such views could temporarily provide financial and spiritual relief to those impacted by a climate crisis. This often materializes in the absence of provision by the official governmental authorities. Moreover, the theoretical accounts provided by religious extremist groups could easily take hold in the consciousness of the affected people due to the lack of environmental education and awareness of the scientific, social and individual measures that can be taken in the face of such a crisis.

The impact of the climate crisis is different from one place to another. Its negative effects in Iraq and the Iraqi Kurdistan Region have manifested in rising temperatures, depleted water resources and sudden flooding, as well as droughts and desertification of agricultural areas. Despite the warnings issued about the crisis by international governmental bodies, as well as scientific, political, and international media institutions, domestic awareness on the issue are minimal. This internal unawareness is evident even among the privileged political elite, the media, and local government administrations, social, educational, and artistic organizations.

Duties and Responsibilities

One of the factors behind this unawareness is that an educational drive for the public to understand the crisis is yet to become an imminently decisive part of the programmers of both the government and civil institutions in Iraq and in the Kurdish region. This is despite the evidently serious threats the climate crisis poses on the future of those areas.

The lion’s share of the responsibilities is with the governmental institutions, given its control of the industrial, infrastructure and other sectors that are the major sources of CO2 and the emission of other greenhouse gases. To name but a few, government institutions are responsible for gas flaring, waste collection methods, electricity generators, cement production or the authorization of the use of countless vehicles in our areas, among others.

The second level of responsibility is with society as the action of each individual generates an amount of greenhouse gases, or carbon footprint, the reducing of which is achieved through recycling and other measures that individuals can take as a duty to mitigate the impact of this crisis, and protect the future of his/her environment, family and wider society. For example, fluorinated greenhouse gases generated from the overuse of appliances such as private air conditioner units, and the production, use and dumping of plastics exacerbates pollution of the climate and contributes to rising temperatures.

The largest scientific study on climate change by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2021 concluded that it was “unequivocal” that human activity is responsible for global warming and changes such as sea-level rises, which are irreversible. On a hopeful note, it pointed out that there was still hope that the impact of the climate crisis could be curbed by emission of greenhouse gases.

Consequently, governments and civil society organizations in many parts of the world have come together around numerous UN projects to address the issue of cutting our carbon footprint. It is important for the whole of society to be aware of the impact of the climate crisis, as eventually an advocacy unit from society will have to gain the power to pressure its government to divert its environmental policies. What exists in our regions is the scarcity of environmental education, which is alarming given how the UN’s Global Environment Outlook 6 (GEO-6) “identified Iraq as the world’s fifth most vulnerable country to decreasing water and food availability and extreme temperatures”.

In a 2019 report, Human Rights Watch (HRW) cited the UN Environment Program as having warned that, “Iraq is currently losing around 25,000 hectares of arable land annually”. That is not a low figure when 1 hectare is 10,000 square meters of land. Worse, in this case as it concerns arable land.

Unfulfilled promises

The crisis has appeared in the discourses of the political authorities in the central Iraqi government and the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region in the north over the past two to three years. However, their pledges made over tackling the issue appear to have been no more than unfulfilled promises, likely made to content foreign diplomatic ties and international media interests.

Months before Iraq became a member of the Paris agreement in December 2021, the then president of Iraq Barham Salih announced the “Mesopotamia Revitalization Project” to tackle the climate crisis. The project highlighted tackling the climate crisis as a national priority. It was probably one of the finest written projects by a government in this region at the time on the climate crisis and Iraqi environmental organizations early on hoped, despite their skepticism, for this project not to be another announcement to only content diplomatic ambitions and the self-image of the Iraqi government in the media. However, the initial skepticisms were not in vain. When a new president and government cabinet was appointed, this project lost its attractions and it has not been mentioned since. The eradication of environmental illiteracy in this century is as crucial as the eradication of illiteracy itself in the previous century. It is still unclear what that government project had offered in terms of Iraq’s own public education on the environment.

The incumbent Iraqi Prime Minister has ranged alarm bells over water shortages, first in a speech to Baghdad International Water Conference in May 2023. He called for urgent international intervention to curb the water crisis facing the country. He said this issue was a priority of his government, without elaborating on how.

The prime minister pledged new measures for agricultural irrigation techniques that he said Baghdad was to acquire from developed countries. He also highlighted that Iraq was in negotiation with neighboring countries to find a solution for the water crisis and deemed those joint regional efforts as positive. However, he did not dwell on the problems with those countries, likely due to diplomatic sensitivities and his actions since taken power have proved contrary to his promises

Lack of budget

The Iraqi parliament has passed a three-year budget bill as the country's largest federal budget, which Sudani had praised for having helped ease political tensions over financial distribution. However, it does not include any specific budget share to tackle the climate crisis in Iraq or in the Kurdistan region.

Before the federal budget was approved, the Green Iraqi Observatory was one of the organizations reported to have highlighted that MPs had put up nothing for debate in the draft budget bill on issues of “desertification”, “pollution” or the “climate crisis”.

In November 2022, the World Bank Group’s Country Climate and Development Reports (CCDP) said it “estimates that Iraq would require around US$ 233 billion in investments by 2040 to respond to its most pressing development gaps while embarking on a green and inclusive growth pathway.” In the first sentence introducing the findings of the report, the international agency could not be bolder in its predictions, saying that, “climate change, in particular increasing water scarcity, could further threaten Iraq’s fragile social contract under an oil-led growth model that has been a source of economic volatility”.

The highlighting of those issues should not be surprising when in December 2021 it was the Iraqi government’s minister of water resources who warned that the Tigris and Euphrates rivers could dry up by 2040, as a result of climate change and declining water levels.

UN’s Iraq envoy Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert in a 2023 report to the UN Security Council warned that, “if current trends continue, Iraq will only be able to meet 15% of its water demands by 2035”.

The Iraqi ministry of water resources labelled the curbing of the flow of water from Iran as a major obstacle and formally asked the Iraqi foreign ministry to file a lawsuit against Iran at the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Environmental activists at the time considered the move unserious, stressing that it was no more than boasting to the media by the Iraqi ministry and that Iraq has the same issue with Turkey as well. Later, no step was taken in that direction by Iraq on Iran.

The flattery statements that federal Iraqi officials have made in the media on the climate crisis for diplomatic purposes has also been observed among the officials of the semi-autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan region, governed by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

In June 2023, a high-level UN delegation met Iraqi Kurdistan President Nechirvan Barzani in Erbil and according to a statement by the Kurdistan region presidency office, both sides had labelled climate change as a “serious crisis that has a major impact on Iraq”.

The Kurdish presidency’s statement did not explain if the crisis was as serious, then what did the regional Kurdistan president suggest to tackle the crisis. The routine statements from the presidency would have highlighted such a suggestion if it was discussed at the meeting.

Water withholding from Iran, Turkey

The Saudi-based International Institute for Iranian Studies has pointed out from the research of one of its academics in 2019 that Iran was that year set to build 13 new dams, underlining that in the past three decades Tehran had built over 600 dams in Iran. The research concluded that the water crisis could trigger a long-running political dispute with neighboring Iraq. It said in such a case water diplomacy alone may not be enough to end such disputes.

What that research did not mention is that Iran’s own vocal cry over water scarcity due to large dam building projects by Turkey, which Iraq and Syria as well as environmental organizations have long brought to the attention of domestic, regional and international media. The former president of Iran, Hassan Rouhani, called on Turkey to halt its dam building projects on the Euphrates and Tigris given the destructive outcome for Iran. Media outlets in Iran have since continued to highlight the negative consequences of Turkish dam building projects in a strong tone.

Both Iraq and Syria have since 2018 warned that the level of water of both rivers has dangerously reduced. When water ministers of both countries met in May 2021, Iraqi Minister of Water Resources Mahdi Rashid Al-Hamdani said that water flow of the water of Euphrates and Tigris from Turkey had reduced by 50%, adding that Iran had reduced the flow of water to Darbandikhan dam to “zero” and reduced the flow to Dukan dam by 70%. Those two dams are in the Iraqi Kurdistan region.

Syria’s water resources minister, Tamam Raad, that same month visited Syria’s eastern Deir al-Zour and called on Turkey to release the flow of the Euphrates based on Turkey-Syria agreements, saying that the current flow of the river from Turkey was not enough for drinking water and agricultural irrigation.

The agreement the Syrian minister had mentioned was signed between Turkey and Syria in 1987, according to which Ankara must release the flow of 500 cubic meters per second of the Euphrates into Syria. However, Turkey has reportedly only allowed the flow of 200 cubic meters per second in recent years.

Meanwhile, the territory controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) of the self-proclaimed Autonomous Administration of North East Syria (AANES), has witnessed the gradual losing of its once arable land near the banks of River Euphrates to droughts and desertification to the river’s low level. The region was long known as Syria’s breadbasket for its flourishing agriculture.

The Syrian Kurdish Hawar News Agency (ANHA) reported in June 2023 that the withholding of the flow of the Euphrates by Turkey had resulted in the river drying up in the Kobane area, where the low level of water had resulted in the pollution of the environment. This, ANHA said, spread disease among the local population.

Local health officials told ANHA that the health centers in the area each day recorded dozens of cases of poisoning caused by the river’s polluted water. In the small town of Qanayaa (Kanaja), which is 30 kilo meters or km from the larger town of Kobane, the health center received up to 10 cases of poisoning daily, it said. A total of 719 cases had been officially registered in the area in the first six months of 2023, according to local officials.

Warnings have repeatedly come out from Syria and its Kurdish-led Rojava region of the AANES that Turkey uses the reduction of the flow of the Euphrates as a “water war”. The Syrians have also highlighted that since the end of 2019, after Turkey’s invasion of Serekani (Ras al-Ain), the Turkish army and the Ankara-backed Syrian armed groups in charge of the Alouk water treatment facility had shut down the facility over dozens of times intermittently, each time leaving over 1 million people in the Hasaka province without drinking water. The last time they shut down the facility was days ahead of the Islamic Eid al-Adha on 28 June 2023.

Syria as an official government has raised the issue at the UN. Damascus officials repeatedly did so during the Covid pandemic at the UN, but nothing of substance has been implemented by the international community on the issue. The shutting down of the facility in June revealed that the Turkey-backed groups would close the water treatment facility as and when it fits them.

Iraq, KRG as cautious observers

It is claimed domestically that it was also the Turkish building of the Ilisu Dam that had affected the flow of the Tigris into Syria and Iraq. It is the second largest dam in Turkey after the Ataturk dam. Its construction is part of a series of dams built as part of the Southeastern Anatolia Project, which also covers Turkey’s Kurdish region. It was this dam that flooded the 12,000-year-old town of Hasankeyf, in addition to the expected uprooting of around 80,000 people from 199 surrounding villages, Reuters reported in 2020.

Iraq very cautiously highlights the role of Turkey and Iran for its water shortages due to its relations with both sides on other issues. The Iraqi Kurdish KRG also does not project a strong independent stance on the issue, which is likely due to its leading political party’s attachment to Turkey.

What has happened in Syria and the Syrian Kurdish-led AANES region paints a disappointing picture for Iraq too. This is because the experience here has clarified that the level of water allowed to flow from the rivers into a given territory is related to the presence, or the absence of, other interests desired by the water withholder.

KRG dams, an extra barrier?

The KRG has begun building dams amid this climate crisis, labelling it as a mechanism to provide food security. When on 24 June 2003 KRG Prime Minister Masrour Barzani laid the foundation stone of the Bastora dam in Erbil province, he said that more dams will be built for water, energy, agriculture and even attract tourism.

It was interesting that he urged the federal Iraqi government to assist in renovating existing dams and help build planned new dams in the Kurdistan region, inferring that Baghdad should be grateful for how the larger dams in Kurdistan, Darbandikhan and Dukan, benefit the rest of Iraq as well.

His call on Baghdad is related to how the KRG’s agriculture ministry previously tried to have Baghdad pay for the construction of 17 dams and include the expenses in the federal budget of the incumbent Iraqi government cabinet of Prime Minister Muhammad Shiaa al-Sudani.

Iraq has apparently agreed for three dams to be built in Kurdistan as part of its dam-building projects. This is yet to be a conclusive decision given that the federal budget law continues to be a contentious issue among rival political quarters, with complaints and proposed amendments by all sides undergoing a continuous political process in Baghdad.

The construction of the Bawanur dam near the town of Kalar officially began in 2013 with a budget of 234 billion Iraqi dinars (approx. $178.5 million) to be completed in 2018. Yet in 2020, only 15% of the dam had been constructed. It is not known whether the obstacle that had hampered its construction was corruption, disputes between the two ruling parties, Kurdistan Democratic Party and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, the region’s financial crisis, Iraqi federal government’s objection or Iran’s concerns, given the proximity of the dam to the Iranian border.

In December 2019, the KRG decided to pay for the completion of the building of dams whose construction had halted. On 12 July 2021, the KRG decreed spending over 13 billion Iraqi dinars (approx. $10 million) to finalize the completion of 12 dams, five in Erbil, four in Sulaymaniyah and the Garmiyan area and three in Duhok. The heads of KRG dams, Akram Ahmed, said the money provided would complete the construction of four dams and that another six would see significant development prior to complete construction. That same official said in 2019 that the KRG provided 33 billion Iraqi dinars (approx. $25 million) to complete the construction of 11 dams.

A major question is to what extent the federal Iraqi government would endorse the building of the KRG’s own dams, excluding the three dams that Kurdish media reports have said that Baghdad would apparently build at some point in the Kurdish region.

The Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) said in a May 2023 report that the KRG had decided in 2022 to build four large reservoir dams reportedly with Baghdad consultation. The CSIS report warned that “as upstream dams within Iraq continue to restrict water to communities downstream, water could become a flashpoint for tensions and conflict, especially as the water stress worsens”.

The Fikra Forum of Washington Institute for Near East Policy in a 2020 report highlighted that “water shortages have the potential to inflame disagreements” between the KRG and the federal Iraqi government.

Dams pose as much threat as their usefulness if they are not properly built and when they are targeted to be exploded in war. The Mosul dam is today considered the “most dangerous dam in the world” because of its technical problems. In 2016 at the height of the Islamic State (ISIS posed a much larger threat than ISIS itself amid the war.

Moreover, the public also has the right to question the security of dams, especially when armed clashes between rival political armed groups across Iraq a far-fetched possibility is not. And as it stands, holding back IS resurgence remains to be the top security priority for both the official Iraqi and Kurdish armed forces and the international coalition forces stationed in the country.

Alarming Issues

Since 2014 in some Kurdish areas and others in Turkey, torrential rain has been causing flooding of the populated areas in June and July months during the summer heat. This was unheard of a decade earlier. In March 2023, flooding in Urfa and Adiyaman killed at least 14 people among those who were earlier displaced by a deadly earthquake a month earlier.

A heavy dust storm (also sandstorm) hit Iraq in May 2023 and the health authorities in Kirkuk announced that 63 people had visited their health facilities due to various conditions suffered from the dust storm, including 12 children. On the same day, the director of meteorology and seismology of Sulaymaniyah said a wave of dust storm hit southern and central Iraq and its effect had reached Garmiyan (next to Kirkuk) and Sulaymaniyah and Erbil. But he did not mention how dust storms are a fact accelerated by the climate crisis and a problem from which suffers neighboring Iran and Syria, as well as the other countries such as Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), among other Gulf countries. Dust storms in Iraq and Syria in 2022 killed at least six people, hospitalized thousands, and suspended flights in several other countries.

Iraq’s dry lands in its desert are often pointed at as the main sources from which dust storms originate to other countries, but the problem is that those other countries to which the dust storm travels also have dry land, be it the disputes areas on the edge of the KRG or Kurdish areas in neighboring countries or, parts of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, among others. Experts agree that even if dust storm travels due strong wind from Iraq’s desert, the climate crisis has accelerated this phenomenon and that the dust storm’s poisoning of the climate in some countries increases due to air pollution through which it passes, as was the case in the UAE.

Now that this climate crisis has been proven to be a worldwide problem, making biased parochialism will not yield results. Nor will this problem be resolved by approaching it with a politically partisan interest in mind. Also, approaches of unilateral autocratic nature or flattery statements for diplomatic means will only result in regressive steps. Unilaterality will only lead to short-term gains for the politicians and their party cliques or clans. The future of such an approach is disastrous, in Iraqi Kurdistan it would mean remaining in the current situation in which the KDP and the PUK accuse each other over who funds garbage collection in this or that city in their respective areas of influence.

Exit strategy options

Hence, concretely it is suggested to:

- Making efforts to exit a crisis or mitigate its impacts provide opportunities, and this crisis carries several opportunities if the Kurds want to rally around a schematic plan to that end. The first step is to priorities environmental and humanitarian solidarity. The nations living on the banks of the basin of the rivers Euphrates and Tigris, at center of which are the Kurds and others, have no choice but to overcome the dividing lines of ethnic, religious and political tensions to save the rivers and reduce the threat that the climate crisis poses to life.

- The climate crisis has a global dimension and this can enhance the Kurdistan region’s posture at an international level. The Kurdish leadership must take to Baghdad the cases of environmentalism and climate change as top priorities.

- This is also true for the Syrian Kurdish Rojava region governed by the AANES, especially where there is a lot of theoretical advocacies for ecology and a Green future as political identity, even though the political dynamics of the ongoing war in Syria has strongly shut the doors that lead to opportunities in comparison with the Kurdistan region in Iraq.

- For the Iraqi Kurdistan region, the first step is to open up to Baghdad to work towards a coordinated framework with the help of international institutions, so the KRG can play a role under the official status of the Iraqi government at the UN and other international agencies.

- Moving towards a solution and mitigating the effects of this crisis can also expand the opportunities for political reconciliation between the Kurds and the central government.

- In the case of the Kurdistan region, Baghdad's failure to respond to environmental protection projects with international organizations gives the KRG international legitimacy to seek mediation from the UN, the European Union (EU), humanitarian organizations, as well as human rights and environmentalist agencies.

- Society also has a duty to fulfil. If the political authorities are indifferent to the education of individuals in schools, mosques and government institutions, then families, students, university teachers, religious figures, activists, media, civil society organizations, writers and artists have a duty to awaken themselves and awaken our conscience about the climate crisis. Also, learning to act to mitigate the impacts of the climate crisis is as much a religious duty as it is a humanist one towards the future of the whole of society.

- A strong Green political entity is yet to emerge in the Iraqi Kurdistan region and climate change is yet to be integrated into the intellectual ideology and policies of the key existing political parties there. It is only among the Kurdish parties in Syria and in Turkey that environmentalism features in their political worldview. The Kurdish parties in Iraq must turn tackling the climate crisis into a core ideological agenda. While practical opportunities to realize environmentalism is scarce in Rojava due to the war in Syria and in Turkey’s Kurdish region to the denial of Kurdish political rights, there is an ample opportunity in the Kurdistan region of Iraq to recognize, realize and organize Green politics.

- A Kurdistan National Congress should be held to discuss environmental issues, climate change and global warming. Broad cooperation between all the political forces of all the four Kurdish regions is necessary so that each political entity incorporates these issues into its agenda debated in its media and among its public sphere.

- Civil society organizations can also act outside the political parties and government to build a bridge between their own communities and the international organizations and communities that address the mitigation of the global climate crisis.

Curbing the impact of the climate crisis needs a political approach that overcomes ethnic, religious, sectarian lines. It is about a balancing act for all living beings. And, within that balance our lives are entirely linked with the existence and nonexistence of all animals, water sources and plants. This is why the concept of “live locally and think globally” has never been as meaningful as now amid this climate crisis in which the fate of humanity faces a dark future. A different worldview is needed than the current one at play in Kurdistan, Iraq, and the wider region. A perspective that has the capacity to propose strategic educational projects and local awareness under a long-term agenda for local, regional, and international agencies. Moving in this direction will bring many positive opportunities, even for those who view the world only politically.

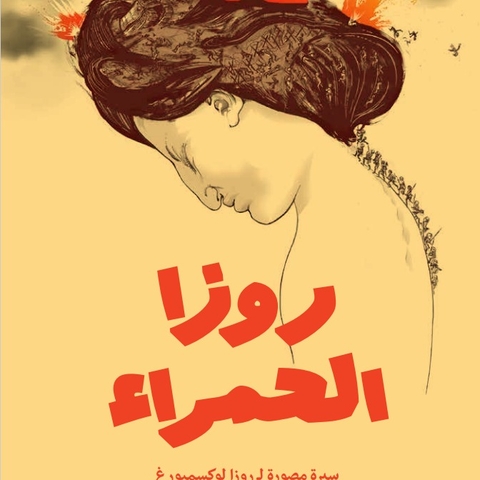

* Initially released in Kurdish, this report is part of critical media reporting and analysis that has began in 2023 between Kurdistan Times and the Rosa Luxembourg Foundation, who continues to provide financial support for Kurdistan Times.